Library

Browse resources published by our research team.

In addition to full texts of our peer-reviewed articles, our library includes research digests that break down our peer-reviewed articles; in-depth reports that thoroughly examine a topic; commentaries that explain the significance of particular issues in wild animal welfare science; and short communications that briefly survey a field or topic.

Wild Animal Initiative adheres to Open Science TOP Guidelines. Read more here.

Quantifying the neglectedness of wild animal welfare

Michaël Beaulieu's deep dive examines the quality and quantity of mentions of wild animal welfare in the scientific literature and finds it to be a neglected research area.

Questioning the neglectedness of wild animal welfare: passionate claims, illusionary facts, or simple truth?

Wild animal welfare is often suggested to be a neglected research area, worthy of more attention from scientists and policy makers (e.g., Tomasik 2015; Forristal 2022). Considering the general propensity of animal welfare to unleash passions even among scientists (Coghlan & Cardilini 2022), it is important to assess the veracity of these claims. So to objectively assert the need to conduct more research to better understand wild animal welfare and implement sound welfare interventions in the wild, clear evidence (or “stubborn facts” insensitive to people’s inclinations and passions; Adams 1770) supporting the neglectedness of wild animal welfare is required.

Cursory research of the expression “wild animal welfare” in Google Scholar (Nov. 2023) provides 844 outputs, only 7% of which emphasize the expression in their title or abstract. However, such figures may be misleading if wild animal welfare is already considered under alternative synonyms or already incorporated into adjacent disciplines. For instance, the fate of wild animals in response to variable environmental conditions has traditionally been under the scrutiny of conservation practitioners (Brown 2007; Nijhuis 2020). Because conservation studies typically focus on conditions that affect animals in their natural habitat (for instance, environmental conditions changing because of anthropogenic activities and that may be perceived as unpleasant by wild animals), they may theoretically also encompass aspects related to wild animal welfare (Sekar & Shiller 2020). Therefore it is possible wild animal welfare is not so highly neglected, but rather often concealed within existing animal conservation studies. Importantly, because the multidisciplinary field of wild animal welfare includes a variety of approaches, indicators, and taxa, some research areas within this field may be more neglected than others.

Assessing the neglectedness of wild animal welfare

To assess the neglectedness of wild animal welfare, I have conducted a targeted review of the literature in peer-reviewed journals publishing research in animal welfare (three journals: Animal Welfare, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, animal welfare section of Animals) and animal conservation (five journals: Animal Conservation, Biological Conservation, Conservation Biology, Conservation Physiology, Oryx). I selected these journals because of their high visibility and their representativeness in their respective field. I considered a date range of 2013-2022 for the review process, in order to reflect contemporary research on animals. Accordingly, I only included research articles (as opposed to reviews, commentaries) focusing on animals (as opposed to, e.g., plants, policy) in the review of both fields. I identified and classified the study subjects of each welfare science article as “wild” if they were studied in their natural habitat or collected in the wild and then studied in captivity. In conservation articles, I searched for welfare-related terms (e.g., welfare/wellbeing, sentience, emotion, conscious, subjective experience, affective state, compassionate) in both the title and abstract.

Confirming the neglectedness of wild animal welfare

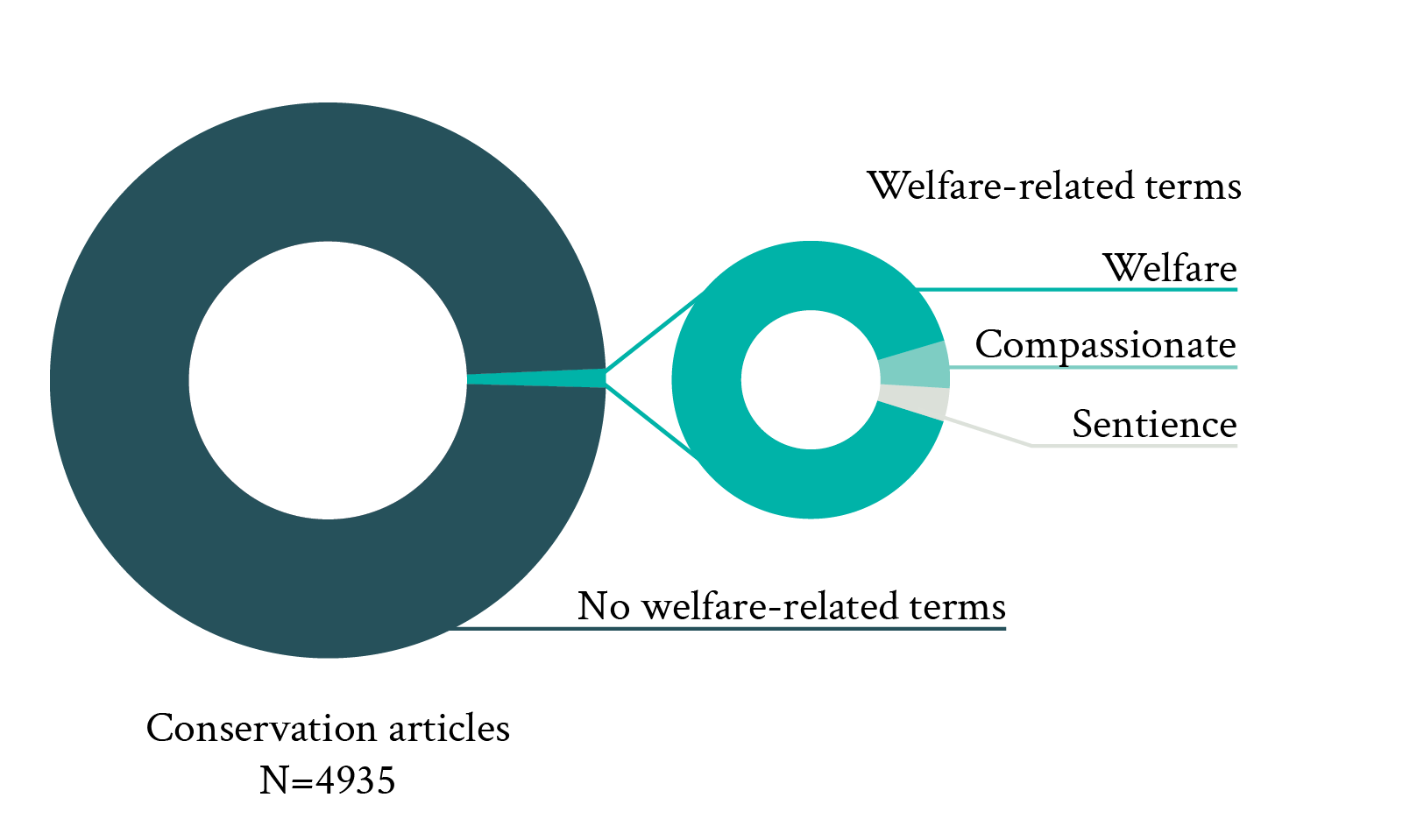

Both the presence of wild animals among all reviewed welfare studies (6%) and the occurrence of welfare-related terms in conservation studies (1%) were very low (Fig. 1). Among welfare-related terms, “welfare/wellbeing” was by far the most commonly used term (90%) in conservation journals. In addition to “welfare/wellbeing,” other welfare-related terms such as “compassionate” (6%) and “sentience” (4%) were also found. However, other welfare-relevant terms such as “conscious,” “subjective experience,” or “affective state” were completely absent. Altogether, these proportions strongly suggest that wild animal welfare is neglected by both the welfare and conservation literature.

Figure 1. Proportion of articles published in three principal animal welfare journals between 2013 and 2022 and including wild animals (left pie, top on mobile), and proportion of articles published in five principle conservation journals over the same period and including welfare-related terms in either their title or abstract (welfare, compassionate and sentience were the only terms found; right panel, bottom on mobile).

Dissecting the neglectedness of wild animal welfare: the example of physiological approaches

To understand how an animal experiences their life in the wild, it is necessary to use approaches that can evaluate and provide evidence of their welfare. Behavioral and physiological markers potentially represent downstream indicators of welfare, and can thus provide insight into the welfare of wild animals (Browning 2022). I focused here on physiological markers specifically, as they may be highly informative (on their own or to complement behavioral approaches) for assessing the welfare of wild animals (see deep dive: Welfare and physiology: a complicated relationship). To quantify the degree to which physiological approaches are also being neglected in wild animal welfare science, I have further examined the welfare science studies previously identified as being conducted on wild animals to determine whether they made use of physiological markers and in which species.

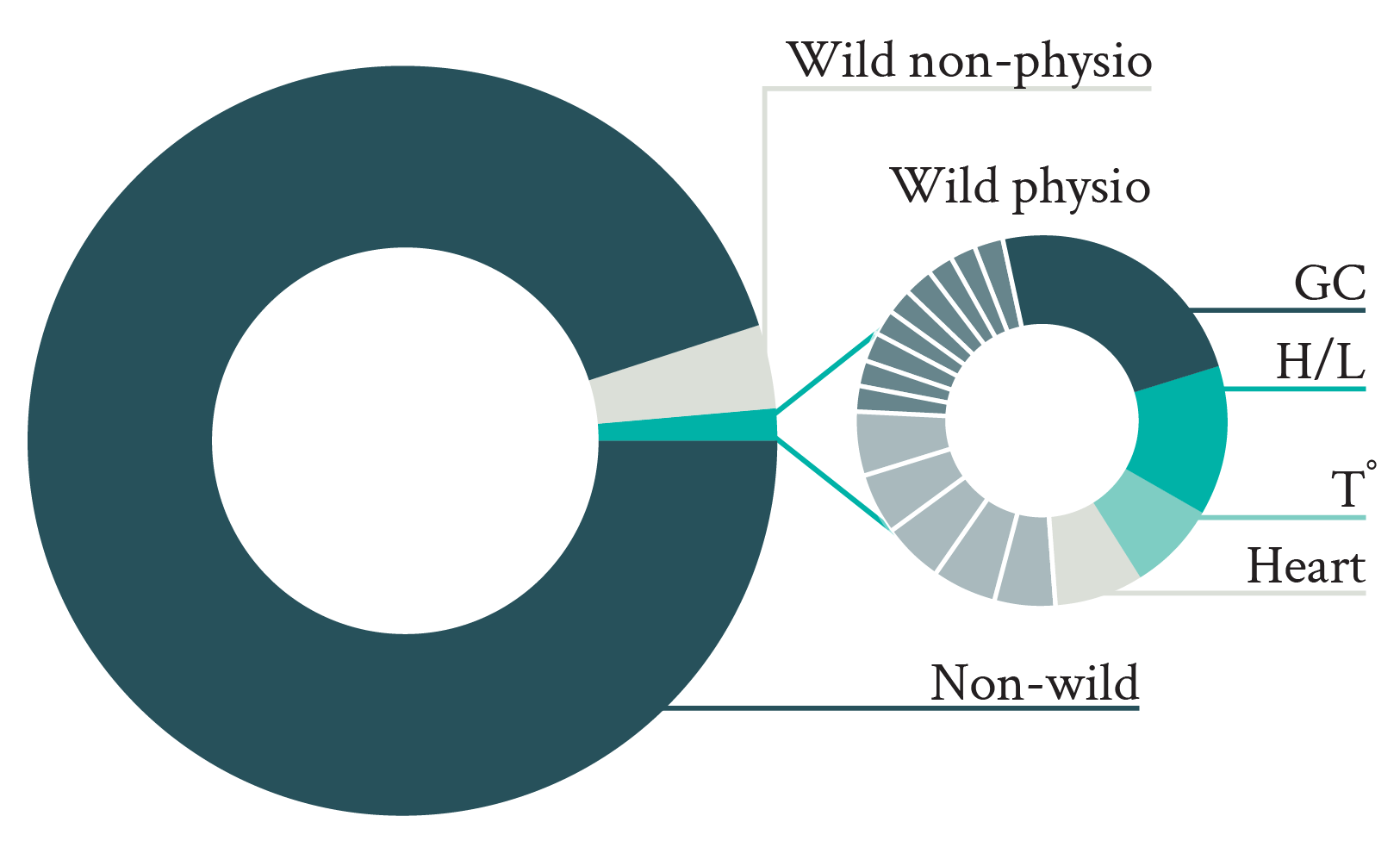

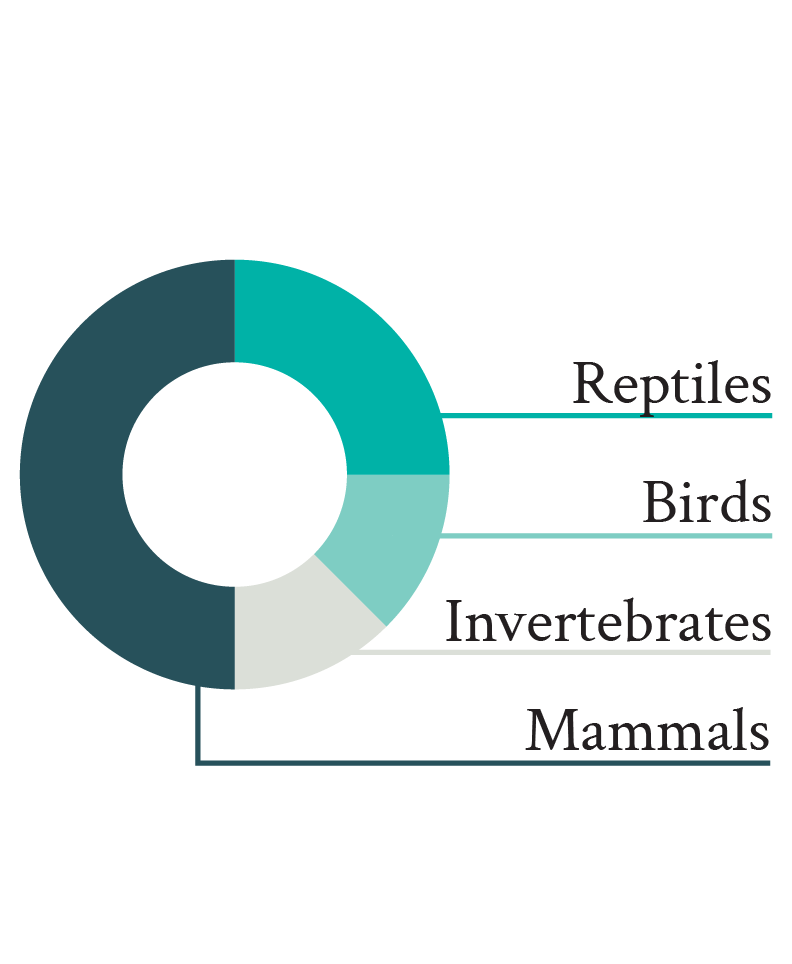

Only 22% of welfare science studies conducted on wild animals included the use of physiological markers (Fig. 2). These results suggest that wildlife biologists either are reluctant to make use of physiological markers in their research relative to other welfare indicators (e.g., living conditions, behavior), or they lack awareness of how to incorporate them. Yet the very existence of the field of conservation physiology, and the numerous studies published, demonstrate that it is possible to measure a diversity of physiological markers in the wild to examine how wild animals are affected by given environmental conditions (Cooke et al. 2013). Nevertheless, despite this potential, thus far such studies have not focused on assessing welfare, as indicated by only 3% of articles published in conservation journals and including physiological parameters mentioning welfare-related terms in their title or abstract. Moreover, the few studies that considered physiological parameters to assess welfare in wild animals focused on a limited number of physiological markers (compared to the vast variety of physiological parameters that could theoretically be measured to assess welfare; e.g., Jerez-Cepa & Ruiz-Jarabo 2021; Whitehead & Dunphy 2022) measured in few taxa, the typical study measuring glucocorticoids in a mammal species (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of articles published in three principal animal welfare journals between 2013 and 2022 and including wild animals (left pie, top on mobile) and measuring physiological markers (striped area). The detail of the measured physiological markers (GC: glucocorticoids; H/L: heterophil/lymphocyte ratio, Tº: temperature) and in which taxa (Invert.: invertebrates) they were measured is illustrated in the right pies (bottom on mobile). For clarity, only the first half of the physiological markers measured in articles on wild animal welfare physiology is annotated.

The overrepresentation of glucocorticoids (and their effects on the H/L ratio; Davis et al. 2008) and mammals among studies on the physiology of wild animals is not necessarily surprising, but their measurement is questionable when examining their welfare. Indeed, even though measuring glucocorticoids reflects a general trend observed in animal stress physiology (MacDougall-Shackleton et al. 2019), the relationship between glucocorticoids and welfare remains unclear (Ralph 2016). Therefore, for glucocorticoid measurements to offer useful insights about welfare, they need to be complemented by additional markers (e.g., behavioral observations). Moreover, even though the imbalance in favor of mammals probably reflects the widespread greater interest in these animals, mammals are relatively rare in nature (ca. 0.1% of all animal species and ca. 0.35% of the whole animal biomass on Earth; Mora et al. 2011; Burgin et al. 2018; Bar-On et al. 2018), and the way they experience their lives is probably not comparable to that of other taxa with very different neural organizations (e.g., more common invertebrates; Paul et al. 2020).

Conclusions

Review of recent literature in key peer-reviewed journals in animal welfare showed that the neglectedness of wild animal welfare is indeed a “stubborn fact” and not just a questionable claim. Importantly, the targeted review of journals in animal conservation also provided evidence that this underrepresentation was not simply an artifact of the inclusion of welfare aspects within animal conservation studies (that were found to refer to animal welfare only anecdotally and superficially). Moreover, within the limited number of studies that did focus on wild animal welfare, the limited use of physiological markers further highlights the neglectedness of valuable methodological approaches and taxa. If allowed to persist, such biases will likely limit our understanding of wild animal welfare, as the strength of this field precisely lies in its diversity of approaches and the range of taxa to which they can be applied. Continuing not to take advantage of such potential would be short-sighted.

The limited availability of welfare science studies focusing on wild animals suggests that there may be resistance or barriers to extending the scope of welfare science beyond the traditional context of farmed, companion, and captive-housed animals. A contributing factor may be that assessing welfare is easier in well-known model species maintained under controlled conditions in captivity (e.g., pigs), compared with their wild counterparts living under uncontrollable conditions (e.g., wild boars). Another contributing factor might also be related to the uncertainty about the capacity of many wild animals to have subjective experiences (e.g., invertebrates, but see Anderson & Adolphs 2014; de Waal & Andrews 2022). Despite these inherent challenges, there is increasing evidence that extending the field of animal welfare to wild conditions is feasible (Harvey et al. 2020), particularly through collaborations among scientists from a range of disciplines, and could have far-reaching impacts for our general understanding of how most animals on Earth experience their lives. In addition to advancing general understanding and increasing available knowledge, wild animal welfare studies may also lead to concrete applications — for instance, by informing stakeholders, refining practices, or modifying legislation impacting wildlife. But the full potential of the field of wild animal welfare will be reached only if scientists branch out beyond traditional norms and consider the full range of approaches and taxa that this field has to offer.

Why cause of death matters for wild animal welfare

In part one of this series, Luke Hecht introduces approaches to studying wild animals’ causes of death, with the goal of making work in this field maximally useful for understanding wild animal welfare.

The most fundamental reason for viewing death as a bad thing is that it deprives individuals of future experiences, assuming those experiences would have been predominantly positive. However, the process of dying is also often painful in itself, and an individual’s death can have additional negative impacts—emotional and material—on others, including family and the broader population.

The costs of a death depend on its cause. Humans are willing to sacrifice periods of healthy life to avoid especially unpleasant deaths, and see various causes of death as more fearsome than others (Sunstein 1997; Chapple et al. 2006). Of course, people’s perception of how much suffering particular deaths would entail may be biased by things like squeamishness; they may assume that because a death is gruesome it must be especially painful. The terminal stages in the process of dying, during which suffering presumably outweighs pleasure, comprise a small fraction of most humans’ lives. Willingness to trade years of healthy life to obtain a quicker, less painful death implies that either the original manner of death must be extremely bad, or that we have an exaggerated sense of how bad dying is.

As recently as the 19th century, only around half of newborns could expect to survive to adulthood (Riley 2005). Many human cultures have had traditions of only conferring names on children when they reached a certain age, potentially because it was understood that most would not survive that long (but that if they did, they would have a decent prospect of reaching adulthood) (Lancy 2014). For example, birth registration was not a legal requirement in the United Kingdom until 1874 (ONS 2015). As average lifespan increases, the dying process represents an ever smaller proportion of human life.

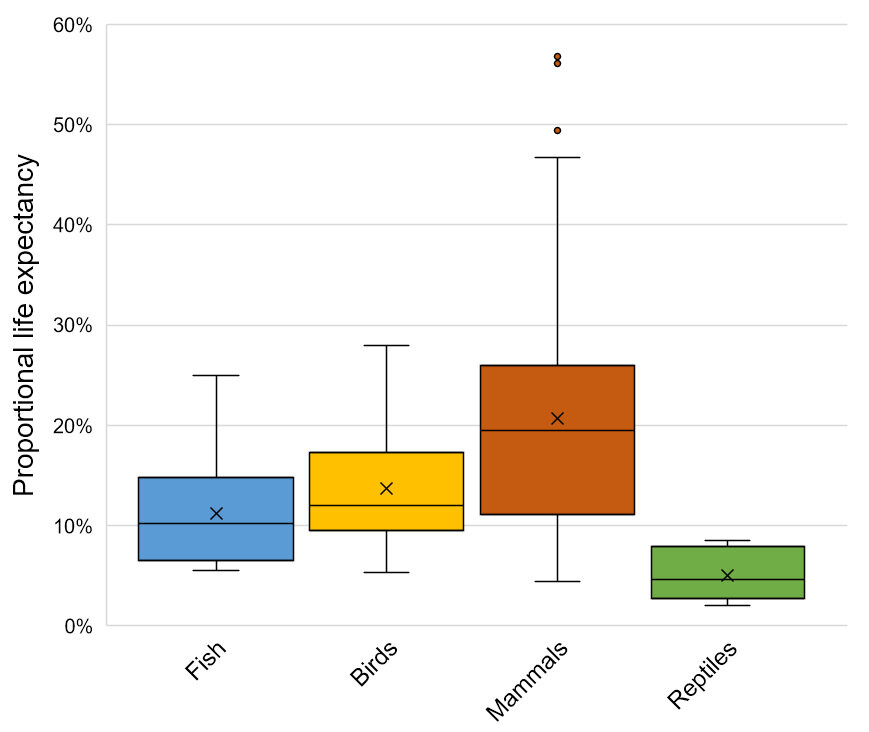

While human childhood mortality has declined dramatically throughout much of the world, most wild animals still die at a young age relative to the longest-lived members of their own species (Figure 1). For these animals, the process of dying may actually represent a substantial portion of their lifetimes, suggesting that, in addition to knowing the most likely causes of death for entire populations, it would be especially valuable to know which manners of death are common among juveniles in specific wild animal populations.

Figure 1: A boxplot showing life expectancy as a percentage of a species’ maximum lifespan for 152 populations of fish (n=16), birds (n=54), mammals (n=72) and reptiles (n=10). Life expectancies were calculated from models found in the COMADRE database (Salguero-Gomez et al. 2016), and maximum lifespans were obtained from AnAge (De Magalhães et al. 2005). Across major vertebrate classes, most individuals live to only 10-30% of the age of the oldest known individuals of their species.

“Cause” of death can be interpreted in at least two different ways: “manner” of death, or “ultimate cause” of death. Both matter for wild animal welfare, but they can be difficult to disentangle in practice. For example, an animal who died during a forest fire may have died by burning or asphyxiation. Other animals may die in the immediate aftermath of a forest fire from dehydration or infected burn wounds. The welfare impact of these different manners of death would likely vary, and it is possible in theory to rank their welfare impacts based on the intensity and duration of suffering leading up to death (Figure 2; Sharp and Saunders 2011). Learning about the precise manner in which wild animals die can help us prioritize hazards to protect them from to reduce instances of the most extreme suffering. On the other hand, it is often easier to estimate the number of animals who died due to an ultimate cause - such as forest fires - than to break this down into specific manners of death. Learning about an ultimate cause of death, and the number of deaths resulting from it, is also useful for prioritizing welfare interventions directed at extending good lives.

Figure 2: An example scheme for grading the welfare impact of different manners of death, taking into account both the severity of suffering inflicted and the length of time it takes for the animal to die. Adapted from work by Sharp and Saunders (2011) on wild animal culling methods.

To minimize the suffering animals experience in the wild, we need to understand how and why wild animals die, paying particular attention to the most numerous experiences: that is, the deaths of juvenile animals belonging to common species. The rates of different causes of death are also valuable to know because even if dying turns out to be a minor contributor to lifetime welfare, or the difference in severity between manners of death is relatively low, substituting one manner of death for another less painful one could improve individual welfare without affecting population size, minimizing the number of variables we need to consider to determine whether an intervention is worth implementing.

In a series of posts to follow, I will review the methods available for studying causes of wild animal deaths and present a selection of published data on cause-specific mortality rates. Finally, I’ll describe some original modeling by former Wild Animal Initiative Intern Anthony DiGiovanni that explicitly considers how cause of death may change along with the size and demography of wild animal populations.

References

Sunstein, C. (1997). Bad deaths. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14(3), 259-282.

Chapple, A., Ziebland, S., McPherson, A., & Herxheimer, A. (2006). What people close to death say about euthanasia and assisted suicide: a qualitative study. Journal of Medical Ethics, 32(12), 706-710.

Riley, J. C. (2005). Estimates of regional and global life expectancy, 1800–2001. Population and Development Review, 31(3), 537-543.

Lancy, D. (2014). “Babies aren’t persons”: A survey of delayed personhood. In H. Otto & H. Keller (Eds.), Different Faces of Attachment: Cultural Variations on a Universal Human Need (pp. 66-110). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Office for National Statistics. (2015). How has life expectancy changed over time? Retrieved from https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/articles/howhaslifeexpectancychangedovertime/2015-09-09.

Sharp, T., & Saunders, G. (2011). A model for assessing the relative humaneness of pest animal control methods. Canberra, Australia: Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

De Magalhaes, J. P., & Costa, J. (2009). A database of vertebrate longevity records and their relation to other life‐history traits. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 22(8), 1770-1774.

Salguero‐Gómez, R., Jones, O. R., Archer, C. R., Bein, C., de Buhr, H., Farack, C., ... & Römer, G. (2016). COMADRE: a global database of animal demography. Journal of Animal Ecology, 85(2), 371-384.