Quantifying the neglectedness of wild animal welfare

Written by: Michaël Beaulieu

Published: November 22, 2023

DOI: https://doi.org/10.71441/7vws-rn93

Suggested citation: Beaulieu, M. (November 2023), Quantifying the neglectedness of wild animal welfare, Wild Animal Initiative, retrieved [date], https://doi.org/10.71441/7vws-rn93

Questioning the neglectedness of wild animal welfare: passionate claims, illusionary facts, or simple truth?

Wild animal welfare is often suggested to be a neglected research area, worthy of more attention from scientists and policy makers (e.g., Tomasik 2015; Forristal 2022). Considering the general propensity of animal welfare to unleash passions even among scientists (Coghlan & Cardilini 2022), it is important to assess the veracity of these claims. So to objectively assert the need to conduct more research to better understand wild animal welfare and implement sound welfare interventions in the wild, clear evidence (or “stubborn facts” insensitive to people’s inclinations and passions; Adams 1770) supporting the neglectedness of wild animal welfare is required.

Cursory research of the expression “wild animal welfare” in Google Scholar (Nov. 2023) provides 844 outputs, only 7% of which emphasize the expression in their title or abstract. However, such figures may be misleading if wild animal welfare is already considered under alternative synonyms or already incorporated into adjacent disciplines. For instance, the fate of wild animals in response to variable environmental conditions has traditionally been under the scrutiny of conservation practitioners (Brown 2007; Nijhuis 2020). Because conservation studies typically focus on conditions that affect animals in their natural habitat (for instance, environmental conditions changing because of anthropogenic activities and that may be perceived as unpleasant by wild animals), they may theoretically also encompass aspects related to wild animal welfare (Sekar & Shiller 2020). Therefore it is possible wild animal welfare is not so highly neglected, but rather often concealed within existing animal conservation studies. Importantly, because the multidisciplinary field of wild animal welfare includes a variety of approaches, indicators, and taxa, some research areas within this field may be more neglected than others.

Assessing the neglectedness of wild animal welfare

To assess the neglectedness of wild animal welfare, I have conducted a targeted review of the literature in peer-reviewed journals publishing research in animal welfare (three journals: Animal Welfare, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, animal welfare section of Animals) and animal conservation (five journals: Animal Conservation, Biological Conservation, Conservation Biology, Conservation Physiology, Oryx). I selected these journals because of their high visibility and their representativeness in their respective field. I considered a date range of 2013-2022 for the review process, in order to reflect contemporary research on animals. Accordingly, I only included research articles (as opposed to reviews, commentaries) focusing on animals (as opposed to, e.g., plants, policy) in the review of both fields. I identified and classified the study subjects of each welfare science article as “wild” if they were studied in their natural habitat or collected in the wild and then studied in captivity. In conservation articles, I searched for welfare-related terms (e.g., welfare/wellbeing, sentience, emotion, conscious, subjective experience, affective state, compassionate) in both the title and abstract.

Confirming the neglectedness of wild animal welfare

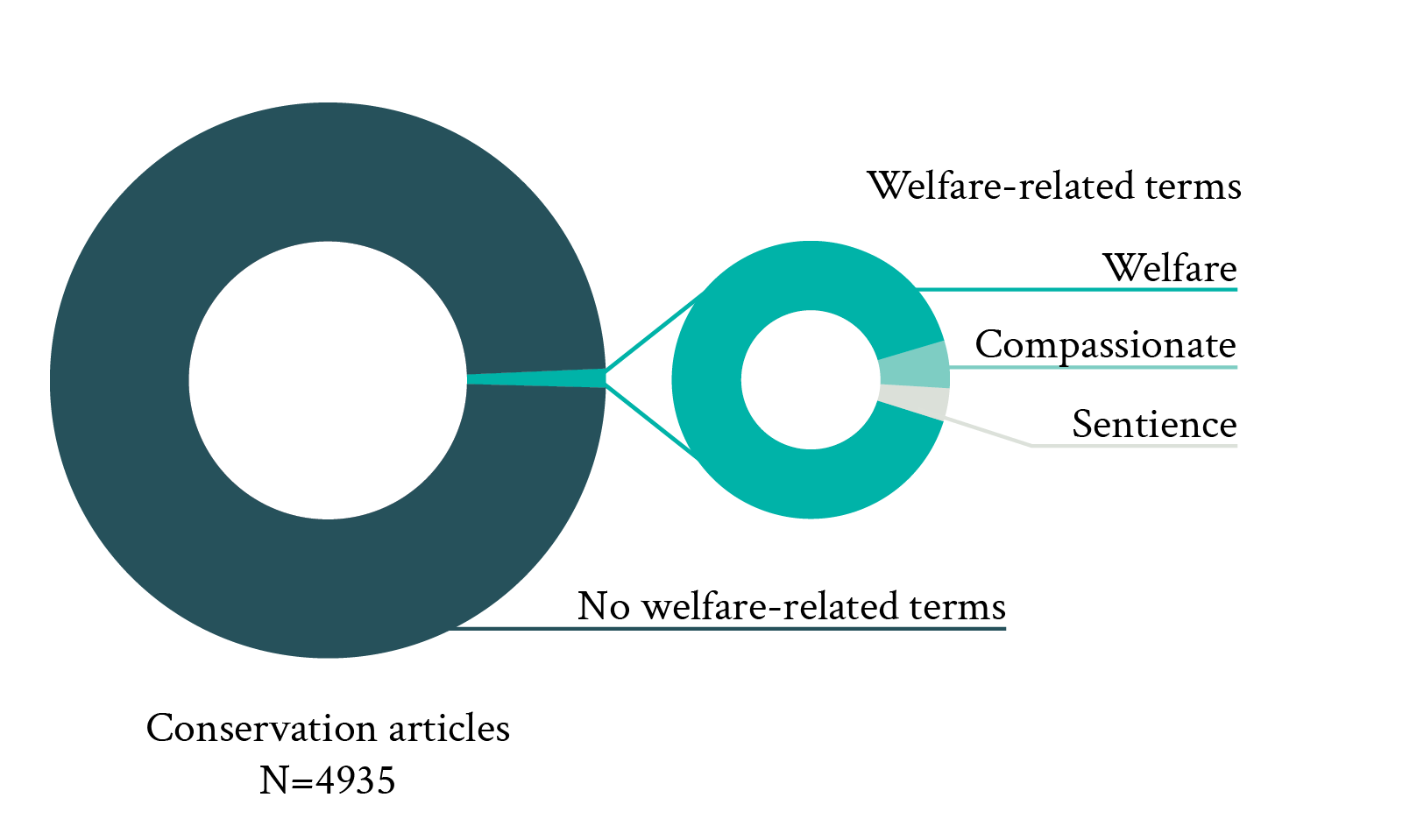

Both the presence of wild animals among all reviewed welfare studies (6%) and the occurrence of welfare-related terms in conservation studies (1%) were very low (Fig. 1). Among welfare-related terms, “welfare/wellbeing” was by far the most commonly used term (90%) in conservation journals. In addition to “welfare/wellbeing,” other welfare-related terms such as “compassionate” (6%) and “sentience” (4%) were also found. However, other welfare-relevant terms such as “conscious,” “subjective experience,” or “affective state” were completely absent. Altogether, these proportions strongly suggest that wild animal welfare is neglected by both the welfare and conservation literature.

Figure 1. Proportion of articles published in three principal animal welfare journals between 2013 and 2022 and including wild animals (left pie, top on mobile), and proportion of articles published in five principle conservation journals over the same period and including welfare-related terms in either their title or abstract (welfare, compassionate and sentience were the only terms found; right panel, bottom on mobile).

Dissecting the neglectedness of wild animal welfare: the example of physiological approaches

To understand how an animal experiences their life in the wild, it is necessary to use approaches that can evaluate and provide evidence of their welfare. Behavioral and physiological markers potentially represent downstream indicators of welfare, and can thus provide insight into the welfare of wild animals (Browning 2022). I focused here on physiological markers specifically, as they may be highly informative (on their own or to complement behavioral approaches) for assessing the welfare of wild animals (see deep dive: Welfare and physiology: a complicated relationship). To quantify the degree to which physiological approaches are also being neglected in wild animal welfare science, I have further examined the welfare science studies previously identified as being conducted on wild animals to determine whether they made use of physiological markers and in which species.

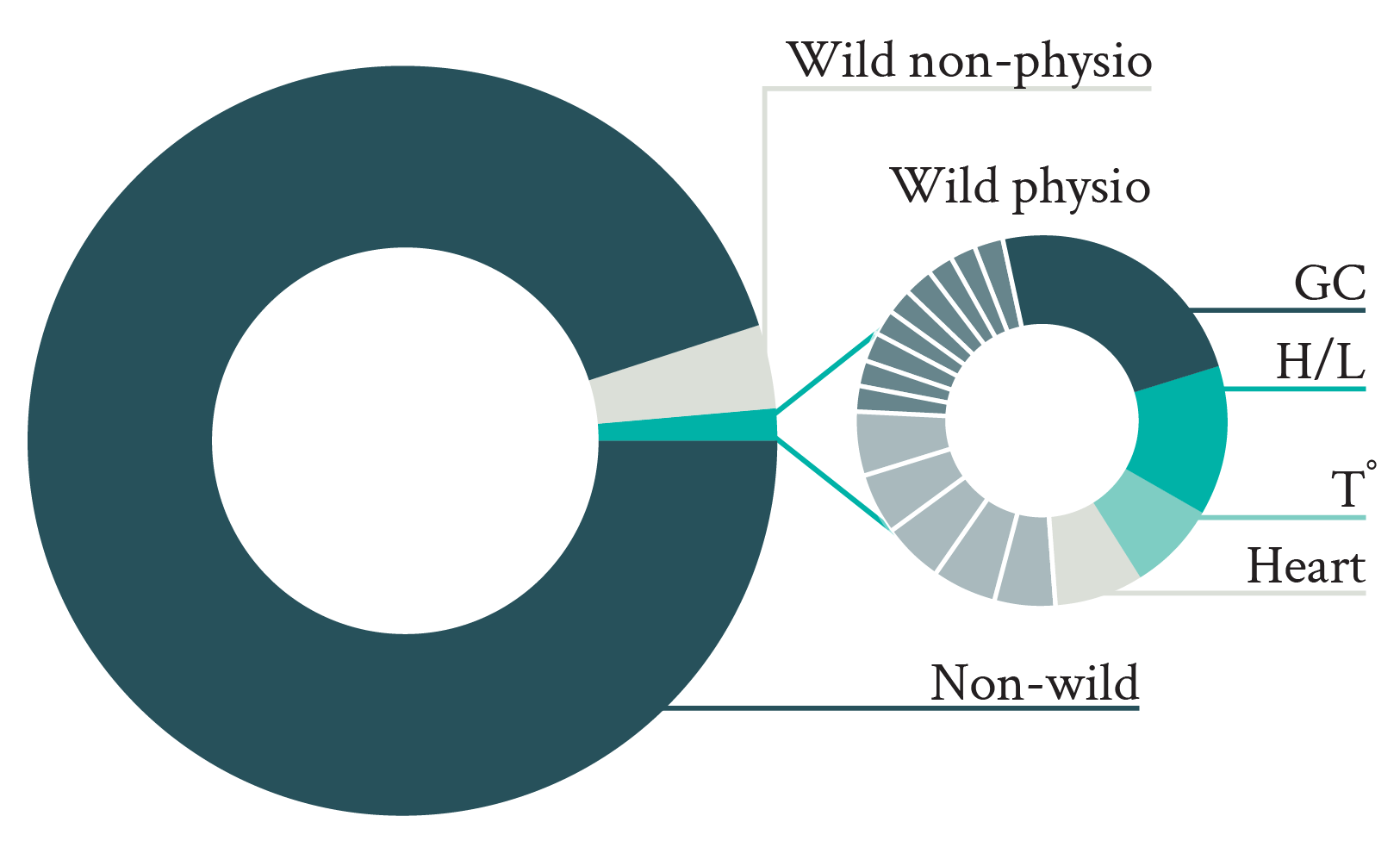

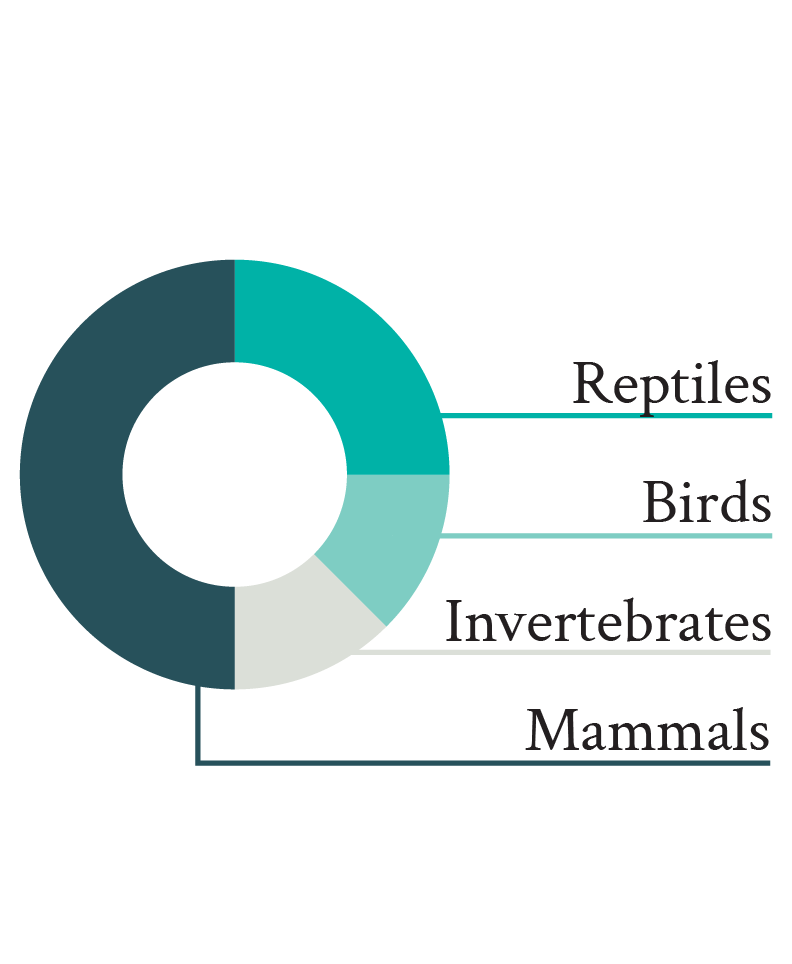

Only 22% of welfare science studies conducted on wild animals included the use of physiological markers (Fig. 2). These results suggest that wildlife biologists either are reluctant to make use of physiological markers in their research relative to other welfare indicators (e.g., living conditions, behavior), or they lack awareness of how to incorporate them. Yet the very existence of the field of conservation physiology, and the numerous studies published, demonstrate that it is possible to measure a diversity of physiological markers in the wild to examine how wild animals are affected by given environmental conditions (Cooke et al. 2013). Nevertheless, despite this potential, thus far such studies have not focused on assessing welfare, as indicated by only 3% of articles published in conservation journals and including physiological parameters mentioning welfare-related terms in their title or abstract. Moreover, the few studies that considered physiological parameters to assess welfare in wild animals focused on a limited number of physiological markers (compared to the vast variety of physiological parameters that could theoretically be measured to assess welfare; e.g., Jerez-Cepa & Ruiz-Jarabo 2021; Whitehead & Dunphy 2022) measured in few taxa, the typical study measuring glucocorticoids in a mammal species (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of articles published in three principal animal welfare journals between 2013 and 2022 and including wild animals (left pie, top on mobile) and measuring physiological markers (striped area). The detail of the measured physiological markers (GC: glucocorticoids; H/L: heterophil/lymphocyte ratio, Tº: temperature) and in which taxa (Invert.: invertebrates) they were measured is illustrated in the right pies (bottom on mobile). For clarity, only the first half of the physiological markers measured in articles on wild animal welfare physiology is annotated.

The overrepresentation of glucocorticoids (and their effects on the H/L ratio; Davis et al. 2008) and mammals among studies on the physiology of wild animals is not necessarily surprising, but their measurement is questionable when examining their welfare. Indeed, even though measuring glucocorticoids reflects a general trend observed in animal stress physiology (MacDougall-Shackleton et al. 2019), the relationship between glucocorticoids and welfare remains unclear (Ralph 2016). Therefore, for glucocorticoid measurements to offer useful insights about welfare, they need to be complemented by additional markers (e.g., behavioral observations). Moreover, even though the imbalance in favor of mammals probably reflects the widespread greater interest in these animals, mammals are relatively rare in nature (ca. 0.1% of all animal species and ca. 0.35% of the whole animal biomass on Earth; Mora et al. 2011; Burgin et al. 2018; Bar-On et al. 2018), and the way they experience their lives is probably not comparable to that of other taxa with very different neural organizations (e.g., more common invertebrates; Paul et al. 2020).

Conclusions

Review of recent literature in key peer-reviewed journals in animal welfare showed that the neglectedness of wild animal welfare is indeed a “stubborn fact” and not just a questionable claim. Importantly, the targeted review of journals in animal conservation also provided evidence that this underrepresentation was not simply an artifact of the inclusion of welfare aspects within animal conservation studies (that were found to refer to animal welfare only anecdotally and superficially). Moreover, within the limited number of studies that did focus on wild animal welfare, the limited use of physiological markers further highlights the neglectedness of valuable methodological approaches and taxa. If allowed to persist, such biases will likely limit our understanding of wild animal welfare, as the strength of this field precisely lies in its diversity of approaches and the range of taxa to which they can be applied. Continuing not to take advantage of such potential would be short-sighted.

The limited availability of welfare science studies focusing on wild animals suggests that there may be resistance or barriers to extending the scope of welfare science beyond the traditional context of farmed, companion, and captive-housed animals. A contributing factor may be that assessing welfare is easier in well-known model species maintained under controlled conditions in captivity (e.g., pigs), compared with their wild counterparts living under uncontrollable conditions (e.g., wild boars). Another contributing factor might also be related to the uncertainty about the capacity of many wild animals to have subjective experiences (e.g., invertebrates, but see Anderson & Adolphs 2014; de Waal & Andrews 2022). Despite these inherent challenges, there is increasing evidence that extending the field of animal welfare to wild conditions is feasible (Harvey et al. 2020), particularly through collaborations among scientists from a range of disciplines, and could have far-reaching impacts for our general understanding of how most animals on Earth experience their lives. In addition to advancing general understanding and increasing available knowledge, wild animal welfare studies may also lead to concrete applications — for instance, by informing stakeholders, refining practices, or modifying legislation impacting wildlife. But the full potential of the field of wild animal welfare will be reached only if scientists branch out beyond traditional norms and consider the full range of approaches and taxa that this field has to offer.